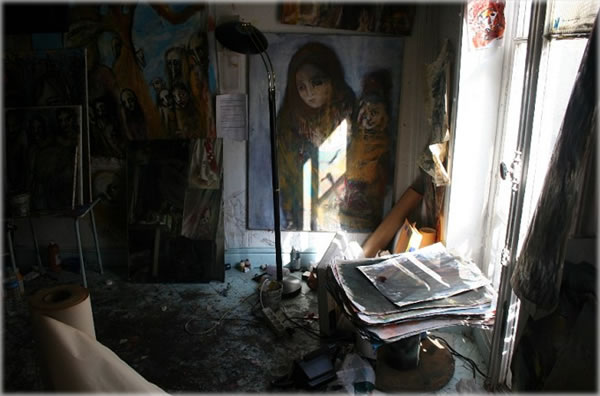

Studio space at 59, Rue de Rivoli. Photo by Eric Francis Farewell, 59 AT SOME POINT when I was living in Paris, a friend named Mona took me for a walk one Saturday afternoon, across the river to the right bank and down Rue du Rivoli. She led me past the high-fashion shoe and clothing shops, though the mob and up to a red, pink and yellow door with the number 59 painted onto it, through the door, and into another world. Some casual looking but serious doormen were working the entrance, and had us sign the 'guest book', which turned out to be an accident disclaimer put there at the behest of the city. I think there was a urinal in the lobby. Inside was another kind of mob: people who showed up to visit the artists in residence at a famous squat that at the time had been there about six years. In other words, back in the fall of 1999, a bunch of politically charged, creatively hypercharged pranksters took up residence in an enormous abandoned building one day and basically set up shop. In case you're wondering how this can be, at least in Paris and London based on what I have heard from participants, it's considerably harder to get someone out of a space than it is for them to get in. Squatters actually change the locks, set up utilities and get mail. Through a combination of cleverness, persistence, sticking together and public adulation, the artists at 59 managed to hunker down for free and establish an institution of the folk-arts in an industrial space very heart of Paris. Inside for the first time, I had the typical response: being overwhelmed. People were calling it a squat, but until I learned the story, I had a really hard time grasping how you could just, you know, do this so overtly for so long. Paintings, sculptures and numerous indescribable combinations of the two, along with various mannequins, installations, concepts, scraps of metal, ideas, sketches, half done things, drawings, silk screen designs, baseball hats, shopping carts, carvings, curved mirrors and hunks of outdated technology exploded out of every doorway. Except, that is, for the meticulously maintained, wide-open studios that had more of a Zen feeling. This is evidence of what happens when you put in charge a bunch of people who honor creativity above everything else. People off the street who had heard a rumor about the place and showed up were poking their noses in everywhere, bustling up and down the spiral stairs that wound around a mobile of several thousand LP records dangling by a cable from the roof five stories down to the ground floor. Every Saturday was at that time open-house day, and most residents would get busy in their studios to greet the public. I dare say it was a zoo for artists. At some point, I wandered away from Mona and into a studio at the end of a corridor. There, a guy named Kit Brown, something of a giraffe who was in town from Philadelphia, was working on his ink drawings in a friend's studio while playing a recording of the Bulgarian Women's Choir on his Macintosh. We became friends on the spot, in that curiously beautiful American way. The Bulgarian Choir recording, which Kit burned and gave me, is still one of my favorites. Talking to him over the next couple of weeks, I began to piece together the story of 59 rue du Rivoli, and started meeting the people who lived and worked there. Paris is a beautiful space, but the pieces of it that would remind you of Picasso and James Joyce are few and far between. They exist, yes. But most of what is fermenting is wine, not creativity. At 59, it was amazing and inspiring to walk in on a group of working artists who were also willing to get together and not just demand the right to exist, but take it for themselves. e | ||||||

|

|